Over the course of just three years, the KISS phenomenon was established: Gene and Paul met Peter, they met Ace, three studio albums were released, and multi-platinum breakthrough was achieved with KISS Alive!. Here is the story of how KISS came to be in the early years of the 1970s.

Gene Simmons and Paul Stanley had given up on Wicked Lester, their eclectic pre-KISS band that failed to excite their record company Epic. By late summer 1972 Wicked Lester were broke and demotivated, and they were told by company boss Don Ellis that the album they had recorded would not be released. This was a blessing in disguise for Simmons and Stanley, who were disillusioned with Wicked Lester’s lack of a cohesive sound and look, and the duo started to audition other musicians behind the backs of their Lester colleagues.

Their manager at the time, Lew Linet, helped them find another rehearsal room in a loft on 10 East 23rd Street in the Flatiron District of Manhattan, where Simmons and Stanley attempted to soundproof the room with egg cartons. “Gene put a mattress in the place so he could sleep over on occasion,” Stanley would remember, “and we had a couple of rickety chairs.” From this cramped and claustrophobic room with no windows, Simmons and Stanley set about refashioning their music and plot their break from Wicked Lester.

“The problem with Wicked Lester was that it was a Frankenstein monster that evolved in the studio. We spent a year in the studio making an album under the direction of a producer who had much more experience than us but who was possibly less focused in a direction than we were. It was all over the place.”

Paul Stanley

Simmons and Stanley first attempted to fire the other three guys in Wicked Lester – keyboardist Brooke Ostrander, guitarist Ron Leejack and drummer Tony Zarrella. The latter, however, made it clear that he was not walking away from the contract with Epic that they had all signed, even if Epic was blocking the release of their album. Simmons and Stanley simply turned around and said, “Then we quit.”

“I honestly can’t explain why we had that clarity and vision, because most people wouldn’t look a gift horse in the mouth. We had a recording contract. We finished an album with a major label. But it wasn’t what we wanted, and we knew it wasn’t right. So Paul and I decided in this quantum leap forward to break up the band and form a new group, which was KISS.”

Gene Simmons

Aside from the fact that this album on a major label was not going to be released, it seems true enough that Simmons and Stanley knew Wicked Lester was wrong for them. As they started rethinking their approach and writing music in their new rehearsal room, songs were coming fast: Future KISS classics “Deuce”, “Strutter”, “Firehouse”, “100 000 Years”, and “Black Diamond” all stem from this 1972 period of recalibration.

“Much of the time Gene and I sat facing each other on the old wooden chairs, acoustic guitars in our laps. Among the first things we worked on were ‘100 000 Years’, ‘Deuce’, and ‘Strutter’. […] My songs tended to be very much chord-based, mainly because my ability to play riffs was fairly limited. So Gene would often supplement some of my songs with riffs. He had a better understanding of how to play notes and runs.”

Paul Stanley

These exploratory songs that Simmons and Stanley worked up in their new rehearsal room had a unity of style and intention about them, unlike the confusing Wicked Lester sound. But to progress along this road, the songwriting duo first needed a drummer.

Peter Criscuola, soon to rename himself Peter Criss, had placed an ad in Rolling Stone magazine on 31 August 1972, offering his services as “rock & roll drummer” for an “original group”. Simmons called him up and proceeded to ask questions about the drummer’s appearance. Image was as important as music by this point, Simmons and Stanley being very eager to put the whimsical nature of Wicked Lester behind them for something more purposeful. Criss responded in style, passing each of Simmons’ questions (“Are you fat? Do you have long hair? Do you have a beard or a mustache?”) on to the people that were partying in his apartment, to general laughter.

“Gene called me while I was having a wild party at my house. And he gave me this whole spiel. Do I dress good? Is my hair long? And the cool thing was that I had the newest velvets and satins because I had just gotten back from my honeymoon in England and Spain.”

Peter Criss

Simmons and Stanley invited Criss to meet them at Electric Lady Studios, and were duly impressed by the fact that Criss looked and dressed like a proper rock star compared to their own hippie-like look. On the face of it, here was someone they could level up with. Criss then invited them to see his covers band play at a sleazy club called the King’s Lounge in Brooklyn. The band was reportedly not good, but Criss’ raspy voice and the way he hit his snare drum real hard made an impression, and the three of them agreed to a formal audition in the Wicked Lester rehearsal loft.

Criss, a few years older and essentially taking a last stab at finding a promising band situation for himself, auditioned with Simmons and Stanley twice. The first attempt was a failure, possibly attributable to Criss having to play Zarrella’s unfamiliar drum set in the loft (unbeknownst to Zarrella, of course), but the second time he brought his own set and the trio clicked. After a couple of months of rehearsals, they played the infamous Epic showcase for Don Ellis and his A&R assistant Tom Werman on 20 November that ended with Ellis consolidating his rejection of Wicked Lester, even in this new guise. The Wicked Lester album would not see release, and there was no chance that Ellis would let the band keep their contract with their new incarnation, but Simmons remember feeling that something good was starting to form.

“It was loose and kind of greasy, like Charlie Watts of the Rolling Stones. Peter didn’t play like other rock drummers. There was almost a big band swing to his sound, but something about it worked.”

Gene Simmons

Simmons, Stanley and Criss kept rehearsing, but they realized that they would need a lead guitarist to fill out the sound that was taking shape. They placed an ad in the 7 and 14 December issues of the Village Voice news and culture paper that read, “Lead guitarist wanted with flash and ability.” A young man named Bobby McAdams brought the first of these issues of the paper to his friend’s house. His friend was a guitar player named Paul Frehley, soon to rename himself Ace Frehley, and he spotted the ad and went for an audition in the band’s Manhattan loft on 8 December.

Even as early as his very first encounter with the men who would be his KISS bandmates, Frehley needed a particular crutch to handle his nerves. His mother drove him downtown for the audition, and Ace jogged off to a nearby deli to buy a can of beer, before getting his guitar and amp out of the car and entering the lobby of the building. “There, alone beside the elevator, I popped the can and chugged the contents.” Clearly a harbinger of things to come, Ace now felt ready to play.

“When I walked in, there was Bob Kulick, Bruce’s brother [Author’s note: Bob’s younger brother Bruce Kulick would join KISS in 1984] … how weird now that I really think about it. I sat in the far corner of the room to give Bob his space. After a few minutes I pulled my reverse Firebird single-pickup out of its gig bag and started to warm up. All of a sudden Gene walks over to me and asks me to put my guitar away. He said I was being rude and making Bob nervous. Anyway, after Bob left it was my turn.”

Ace Frehley

The first song the band asked Frehley to play along with was “Deuce”, which Ace has later named “one of my favorite KISS songs.” Simmons remembers the clarity of the moment when Ace started soloing along: “We finally heard the sound.” Stanley agrees with the inevitability of the occasion: “Ace belonged in the band.” Even if Bob Kulick was a more capable lead guitarist, and seemingly an easier person to get along with, the band chose Ace.

Some sources, including Peter Criss’ then wife Lydia Criss, claim that Frehley was invited to join the band in time for Christmas season 1972, while others suggest early January 1973. Ace himself has stated January in his autobiography, a few weeks after a second meeting and jam on 16 December. At any rate, the band that would soon become KISS was now primed to face the new year with a sense of unity and purpose.

1973

Simmons, Stanley, Criss and Frehley embarked on a grueling rehearsal cycle, playing their limited number of tunes repeatedly for hours on end at least five days a week, which is surely the reason why four less-than-virtuoso musicians became tight enough and well-oiled enough to deliver staged entertainment that eventually wooed the masses. 1973 was also the period when songs like “Deuce” and “Strutter” would be joined by more classics-in-waiting like “Nothin’ To Lose” (co-sung by Simmons and Criss) and “Cold Gin” (written by Frehley, but sung by Simmons), as well as the obscure “Let Me Know” (Stanley’s “Sunday Driver” repurposed for KISS and sung by both Stanley and Simmons). KISS was now a creative cauldron of four distinct personalities, and this period of formation would be the bedrock on which KISStory was built.

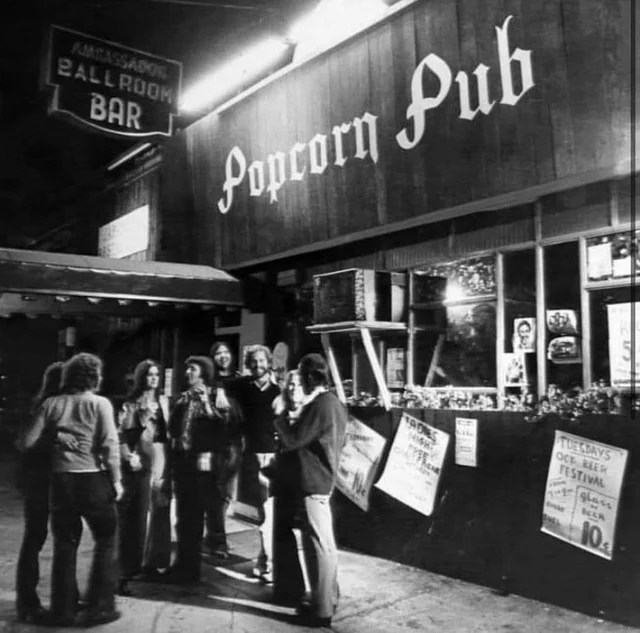

As soon as the end of their first month together, the new band played their first concert. The site was a tiny and crummy club in Queens called Popcorn Pub, which would change its name around this time to Coventry. This was a long way from the hip New York clubs that popular bands would play at that time. But the Coventry establishment, owned by Paul Sub, was the perfect training ground for bands like soon-to-be KISS and later the Ramones among others. The club accepted just about any band and paid a meager 30 dollars a gig, which would become 50 dollars if the band played two sets on the same date.

“Aerosmith was the only act we turned down, because we didn’t want to spend 300 dollars. The New York Dolls were the ones that kept Coventry going. All the other groups that played there, from KISS to the Ramones, didn’t really bring in that many people. […] Nobody knew KISS at the time, they didn’t have a following.”

Paul Sub

“I’ll tell ya, there’s nothing like playing ‘Strutter’ to a bartender and a few girlfriends…”

Paul Stanley

“We still put on make-up, went onstage, and played. We kicked ass for nobody. […] We always stuck to what we practiced and what we worked on no matter what was out there. We still gave it our all.”

Peter Criss

Booked as Wicked Lester, the band played on 30 and 31 January and 1 February, Tuesday and Wednesday and Thursday, sometimes two sets a night. They performed mainly songs that had been recorded for the aborted Wicked Lester album, but also the new songs “Deuce”, “Watchin’ You”, “Baby, Let Me Go”, “Firehouse” and “Black Diamond”. It’s interesting to note that from these very first concerts with the new band, “Deuce” was already the obvious opening number.

As if to underline the major changes that were happening, the three winter nights of Coventry concerts also brought a new and fateful band name. During their first few weeks of rehearsals, the four fresh bandmates had thrown potential names around, wanting to find something self-evident to break completely with Wicked Lester.

“One day Paul and Peter and I were driving around, brainstorming new names. […] I mentioned Crimson Harpoon and Fuck. I thought Fuck was genius. The name of the first record could be You, the name of the second could be It. […] At one point – we were stopped at a red light – Paul said, ‘How about KISS?’ ”

Gene Simmons

“I came up with the name KISS. […] All I could do was hold my breath and say, ‘I hope these guys are smart enough and put whatever ego aside, because this is the right name.’ […] When I said ‘KISS’ it was such a relief to have everybody go, ‘Yeah, that’s good.’ […] No matter where you go, people know that word.”

Paul Stanley

So it was that during their first few concerts at Coventry in late January and early February 1973, Gene Simmons’ and Paul Stanley’s band, previously known as Wicked Lester, officially became KISS. Ace Frehley immediately made the contribution of sketching a logo where the band name’s two s-letters, according to Ace, were styled as lightning bolts. Stanley would subsequently refine Frehley’s idea into the logo as it’s known, where the s-letters are styled more controversially as something that not only resembles the Nazi logo for the paramilitary SS squad, but admittedly looks like a dead ringer for it.

If the original Frehley sketch of the logo that was auctioned off in 2022 is authentic, it seems that his design was already the dead ringer for SS and that Stanley didn’t do much refining after all. Stanley and Simmons would rarely if ever talk about this, their Jewish heritage being a very uneasy match with this logo. Whether they were aware at the time or not, and it is hard to buy them being ignorant of it, the logo would still be obvious enough for authorities to ban its use in Germany and Austria, under the general ban on Nazi symbols.

One particular residue from Wicked Lester that did a lot of good for KISS was their acquaintance with Electric Lady Studios producer Ron Johnson. Not only had he produced the cancelled Lester album, but Simmons and Stanley had also done some work for him as session backing singers with the likes of Lyn Christopher and Mr. G. Whiz. By early 1973, Johnson owed them about 1000 dollars each for their services, and the entrepreneurial duo opted to cash it in as studio time. Johnson agreed to give KISS time at the legendary Electric Lady in March, but he admitted to not being very into the less sophisticated and more direct hard rock that KISS was playing in the wake of Wicked Lester.

“I called Eddie Kramer and told him that I had this wild, almost heavy metal type of act. I told him that he was the strongest hard rock engineer/producer that I knew that could do this.”

Ron Johnson.

South African-born Eddie Kramer was famous at that point for helping guitar pioneer Jimi Hendrix and architect John Storyk to build Electric Lady Studios in New York City’s Greenwich Village, and for engineering all the work of Hendrix in the late 1960s as well as Led Zeppelin’s monumental sophomore record Led Zeppelin II in 1969. He had also worked on the 1967 recording of the Beatles hit “All You Need Is Love”, and he would be head engineer on Led Zeppelin’s ground-breakers Houses Of The Holy in 1973 and Physical Graffiti in 1975. For novices like KISS, this was the heady breeze of working with a master.

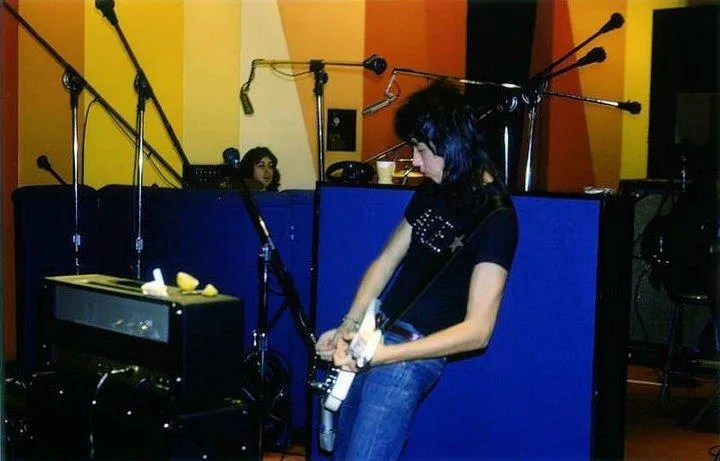

KISS had their first studio experience after just three months together, on 11 and 12 March 1973, with Eddie Kramer and engineer Dave Wittman at the board. Wittman would go on to work on several KISS records in the 1970s and 1980s, and Kramer would of course produce some of the band’s most important work, including the landmark KISS Alive! double live album in 1975. But all of that was in the future. For now, the young and fresh KISS were excited to put five tracks down on studio tape: “Deuce”, “Strutter”, “Cold Gin”, “Watchin’ You”, and “Black Diamond”.

“One day Ron called me and said, ‘Look, Gene and Paul want to form a new band, it’s gonna be a rock ‘n’ roll band. I’m not really into it, but could you do it for me because it’s more your speed?’ […] The studio was pretty new at the time, and I said to Dave Wittman, who was my assistant at that point, ‘We´re gonna do a demo for a new band Gene and Paul have got called KISS.’ I said, ‘We´ll do it the original way that we used to record four-track.’ So we lined up the old four-track machine.”

Eddie Kramer

“We did the tracks in one day and the vocals the next. In a day it was mixed. The Eddie Kramer demos of those songs are better than what turned up on the first KISS album.”

Gene Simmons

“The original demo is much more relaxed than the actual album. I had just joined the group and we’d been rehearsing on a regular basis. In those days, working with Eddie Kramer was a big deal to us ‘cause we were just kids, and he had worked with Jimi Hendrix and Led Zeppelin.”

Ace Frehley

The original KISS demo’s alleged superiority to the later recordings for their debut album is exaggerated. No doubt, the band prefers the more free-flowing and energetic performance in the Kramer demo, but the crude sound and undisciplined arrangements are not as good as the clear sound and tighter arrangements of the album. Most importantly, however, the demo eventually won KISS their first record contract before the end of the year, and it established their relationship with Kramer, which would be integral to their eventual breakthrough in 1975.

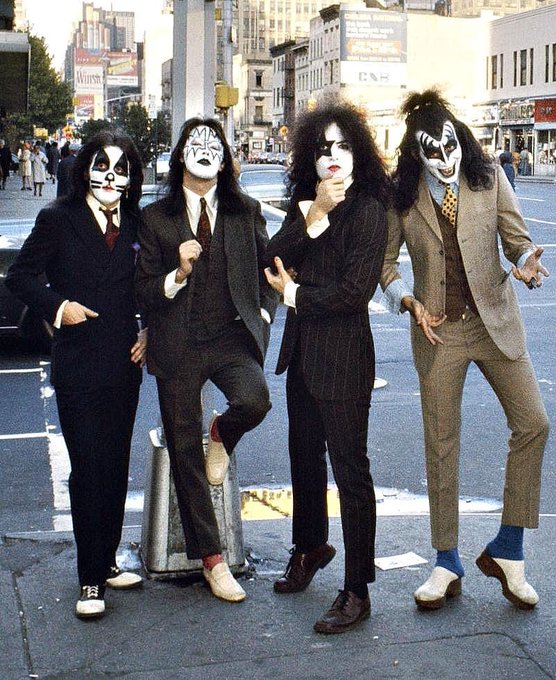

Armed with the demo and a primitive press kit that Simmons put together, KISS set about courting record companies and securing more gigs in the New York area in the spring and summer of 1973. As they charged ahead, they also started developing the visual aspect of their act. KISS would never be all about the music, they would be just as much about the show, and a key part of the show would be make-up.

Another small club that KISS would play frequently in 1973 was The Daisy in Amityville on Long Island, owned by Sid Benjamin. Former Wicked Lester manager Lew Linet was still helping out with this early incarnation of KISS, and Benjamin gave KISS the semi-residency as a favor to Linet. In the spring and summer of 1973, The Daisy would be KISS’ main site for building their live set and their stage act.

“I trusted Lew’s taste and I wasn’t wrong. The audience reaction was great.”

Sid Benjamin

“We’d put on our makeup and costumes in Sid’s office, which we used as our dressing room.”

Gene Simmons

“The phone would ring and we would answer it. People would say, ‘Who’s playing tonight?’ and we´d say, ‘This amazing band called KISS, you’ve just gotta come see them.”

Paul Stanley

During the concerts at the Daisy in mid-1973, KISS was fleshing out their set by still including some Wicked Lester tracks and adding the prog-tinted “Acrobat” and the plainly weird “Life In The Woods”. Of these, the opening of “Acrobat” would turn into “Love Theme From Kiss” on their first album, while “Life In The Woods” would be sensibly dropped. A nucleus of cool songs was now forming, which would provide the backbone of the evolving KISS show, as well as their first few albums: “Deuce”, “Strutter”, “Cold Gin”, “Firehouse”, “Nothin’ To Lose”, “Watchin’ You”, “Baby, Let Me Go” (which would later be renamed “Let Me Go, Rock ‘n’ Roll”), “She” (a Lester tune being KISS-ified), “Love Her All I Can” (ditto), “100 000 Years”, and “Black Diamond”.

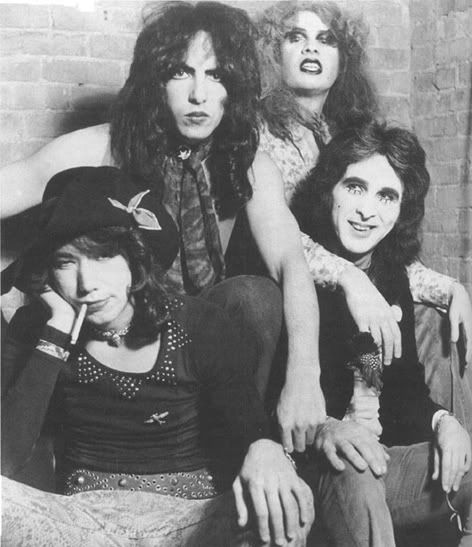

Slowly but surely their use of make-up morphed from the early drag-style glam to the tougher monochrome of whiteface with black and silver eye patterns. Seeing the New York Dolls in concert in March 1973 was instructive for Simmons and Stanley in terms of what they did not want to do: compete in the Dolls’ game. The objective, which would soon be enhanced by their incoming management team, now became to set KISS apart from the androgynous glam of the New York Dolls, and to take the theatrics of Alice Cooper and David Bowie into circus-like overdrive.

“The Dolls were the best-looking band around, and KISS couldn’t compete with the Dolls in terms of trying to be better-looking. So they did something completely opposite, which was to be monsters instead of trying to be attractive.”

Bob Gruen (New York photographer)

“We went to see an Alice Cooper concert and I’ll never forget it. […] We got back to our loft that night and we played and we said, ‘Wait a minute, what if there was four Alice Coopers?’ […] We looked at our personalities and drew from it. Gene was always into monsters. Paul was the true rock star and Ace was definitely from another planet. And I was the total cat.”

Peter Criss

So it was that Simmons, Stanley, Criss and Frehley became The Demon, The Starchild, The Spaceman and The Catman. In the year or so to come their makeup designs would gradually settle in the shapes we know them.

In their ongoing effort to attract attention from the record industry, KISS set up two showcase concerts in Manhattan’s decrepit Hotel Diplomat, on 13 July and 10 August. The second of these shows would be one of the most crucial concerts KISS ever played. Inviting scores of industry people to attend, KISS attracted a key collaborator.

Bill Aucoin had never managed a rock band, but Simmons had invited him on the strength of his work as director and producer for the TV show Flipside, which featured bands performing and being interviewed. Thinking outside the box, Simmons and Stanley reckoned that KISS would need collaborators who understood visual media and presentation at least as much as music. “We needed a manager who had eyes as well as ears,” as Simmons would later say.

“The reason I went to see this group was because Gene sent me these little notes every week, inviting me to see his band, and kept saying that he watched my television show Flipside. […] They wanted to do something different, and they wanted it very badly. That kind of devotion is worth more than anything. I saw that magic in them.”

Bill Aucoin

Aucoin cornered the band after the show, and after introductions and a little talk he invited the band to come see him in his office the following week. He was intrigued by the notion of taking on a job he had never done, but one that seemed to fit well with his show business sensibilities and general level of ambition. Essentially, Aucoin matched the band’s irrational ambition, and he told them plainly when they met in his office: “I’m not interested in working with you guys unless you want to be the biggest band in the world. […] Why don’t you give me 30 days, and if I can get you a record deal and if you want to work together, we’ll go forward.”

The band felt that they had nothing to lose by letting Aucoin try to deliver on that promise. What the coming KISS manager had in mind was to get a deal with someone he already knew: Neil Bogart, who at that time was president of the independent label Buddha Records. But what Aucoin didn’t know was that Bogart was getting simultaneous plugging for KISS from elsewhere. One of his in-house producers, Kenny Kerner, had the job of screening demos for Bogart, going through the pile of cassettes every week to find one or two bands to suggest for consideration. One day in the late summer of 1973, the KISS demo that was recorded by Eddie Kramer and submitted to Buddha by Bill Aucoin, was in this pile.

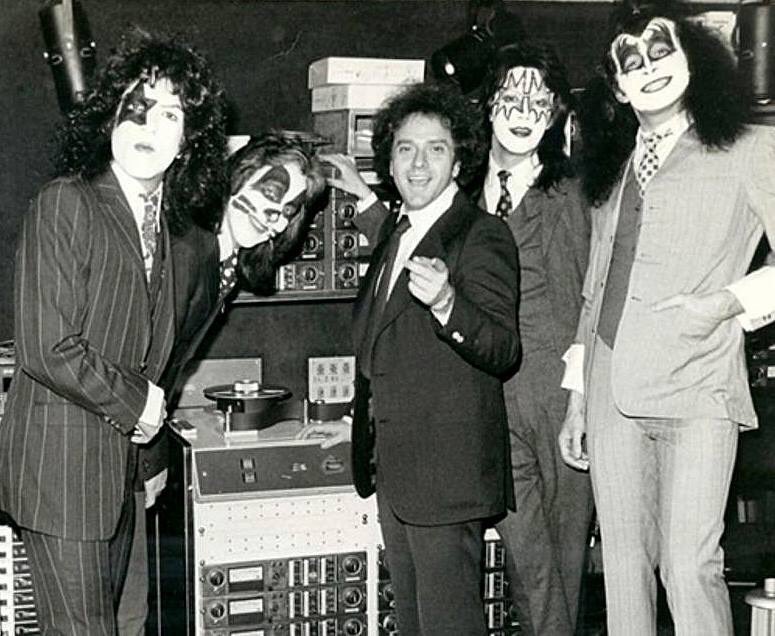

“I used to walk to Neil’s office every week or two and I’d pick up a box of all the tapes that came in the mail and I’d take them home. In one of these boxes […] was a demo reel-to-reel tape from KISS with a black and white photo. […] So I put the tape on, and it was great. It was real raw. […] This was on a Friday. I didn’t even listen to the rest of the stuff. On Monday morning I took the tape and picture back to Neil at Buddha. I said, ‘Neil, this is a great tape. I think we should sign these guys.’ ”

Kenny Kerner

It is interesting to note that neither Kerner nor Bogart had seen KISS’ stage act at this point, only the early 1973 photo with a limited amount of makeup. Their enthusiasm was based on hearing the songs on the demo. The record company man was in, and wanted to offer Bill Aucoin’s new charges a deal. But he wanted to leave Buddha and then make KISS his first signing for his own record label.

“When I first saw them, their music hit me like a bolt of lightning. Their sound, their image, was something I had waited seven years to find. Here was a group whose music and visuals came together in perfect harmony.”

Neil Bogart

Although the contract (in fact a production agreement between Bogart’s new label Casablanca and Aucoin’s new management company Rock Steady Productions) would not be signed until 1 November, KISS had assembled their support team by late September 1973 and signed an artist’s agreement with Aucoin on 15 October. Joining forces with Aucoin in the management of KISS was co-manager Joyce Biawitz, as well as Aucoin’s friend and lover Sean Delaney, a singer and songwriter who would play an integral part in creating the KISS characters and live theatrics, as well as shepherding the band across the country on their earliest tours.

“Bill and I came from theater, film, TV, and advertising – the best possible synthesis of background talents to support a group like KISS. […] Bill and I decided to give KISS’ tape to Neil Bogart when he was still president of Buddha Records. […] I think we told him about their act, but he really thought they were a group he wanted to sign based on the music alone. As he was planning on leaving and forming his own label, he asked if we would bring them to him when he started Casablanca.”

Joyce Biawitz (later Bogart)

KISS’ previous manager Lew Linet had no problem with letting go of the situation, having felt much less of a kinship with KISS than Wicked Lester. “I had some talks with them,” Linet would say many years later. “I told them I knew what they needed, but I didn’t think I could give it to them.” With Epic and Linet out of the picture, and the original KISS line-up established, the way was now clear for the new group to work with Aucoin and Bogart on starting their recording and touring career in earnest.

In retrospect, the logical thing to do would have been to hire Eddie Kramer to produce the first KISS album. He had done a successful demo recording with them that built a solid rapport between Kramer and the band, and which also delivered a record contract. But Bogart wanted to use his own people, and so the production team of Kenny Kerner and Richie Wise were assigned to produce the first KISS album in New York’s Bell Sound Studios in November 1973.

Kramer would return to KISStory a couple of years later, but for now it was the clean and somewhat conservatively inoffensive Kerner and Wise production, solidly assisted by engineer Warren Dewey, that would drape KISS for their first vinyl outing: the eponymous Kiss.

A new round of demos was recorded at Bell Sound in September, with KISS basically playing their entire catalog for Kerner and Wise to select material. As proper recording got underway in November, with the producer duo directing tighter arrangements of several tunes, the songs for the album were whittled down to these: “Strutter”, “Nothin’ To Lose”, “Firehouse”, “Cold Gin”, “Let Me Know”, “Deuce”, “Love Theme From Kiss” (a strange choice in place of something like “Let Me Go, Rock ‘n’ Roll”…), “100 000 Years”, and “Black Diamond.”

“Gene and Paul wrote songs that worked great. They were creative and smart and didn’t hold back or self-censor. I think it’s basically a rock thing – kids that never got any heavy music training could often do great work; it didn’t require a complex skill set. And to me, the real strength of that first album was in the writing.”

Warren Dewey

“Recording the first album was the culmination of everything I’d worked for up to that point. It was exciting because we were doing an album, but pretty early on I thought that the sound was lacking in terms of what I wanted it to be. […] That became a familiar story every time we went into the studio. […] I thought our songs were every bit as good if not better than many, but that sonically our albums were pretty tame.”

Paul Stanley

“Kerner and Wise were the wrong producers to work on that album. We should have stayed with Eddie Kramer.”

Peter Criss

“In hindsight, the first KISS album is fabulous. But at the time I thought it sounded wimpy. I didn’t think the guitars were distorted enough. I didn’t think that the album was aggressive enough.”

Richie Wise

Based on a showcase that KISS had played on 28 September at LeTang’s Rehearsal Hall – for their new management team, producers, and record company president – Kerner and Wise decided that the KISS album had to be raw and unpolished, although some would argue (much like Wise himself does) that the slowing of tempos and lowering of guitar distortion brought a little too much restraint to what was a much more aggressive presentation on stage. In any case, Kiss was quickly recorded and mixed and primed for an early 1974 release, while KISS also worked with their new managers to expand their stage show for upcoming touring.

“Bill Aucoin said, ‘One of you guys should be breathing fire. Which one of you guys doesn’t want to do it?’ And everybody raised their hand. I thought he said, ‘Which one of you guys wants to breathe fire?’ I thought, fuck, I don’t wanna breathe fire. It was a negative question, and I forgot to raise my hand, so I was stuck.”

Gene Simmons

In December 1973, KISS played their final two shows at Coventry, the club where they had started the year as an unknown entity. On New Year’s Eve they played a show at Manhattan’s Academy of Music, supporting Blue Öyster Cult and Iggy and the Stooges. KISS here presented their updated and slicker show, including the lighted KISS logo sign and Simmons’ fire-breathing stunt, appearing as they would look and sound when they embarked on 1974.

1974

It might seem strange in retrospect that KISS and Aucoin opted to sign with a small and brand-new independent label rather than chase a bigger one. There were probably two main reasons for this choice:

First, Neil Bogart’s personal enthusiasm for the band made sure that they were the top priority at a label that desperately wanted to make it big. As Paul Stanley would later say: “There was a feeling back then that Casablanca needed us because KISS was Casablanca.” Bogart had the same desire as KISS.

“It was his idea to have the drums go six feet up in the air. Everybody who joined the KISS team had to be thinking in a like-minded way, and Neil was definitely thinking the way we were.”

Paul Stanley

“We didn’t know enough about the business to know whether or not we had signed a good deal. All we really wanted was to work with cool people, and as far as we were concerned, Neil was very cool.”

Gene Simmons

And second, Bogart’s Casablanca had secured a distribution deal with one of the major record companies in the USA: Warner Brothers. In other words, KISS would be a personal top priority for the Casablanca president, while also benefitting from major distribution. At least in theory, this was a double price, although there would be complications to the Warner Bros set-up within a short time. But for now, KISS were poised to release their debut album and to tour the country in any way that Aucoin and their new booking agents at ATI (American Talent International) were able to arrange.

Released on 8 February 1974, Kiss did little to trouble the sales charts. But Aucoin put effort into getting the band on tours throughout North America, either in small venues on their own or as support act for the likes of Argent and Savoy Brown in bigger places. Road stories are plentiful in many official and non-official KISS books, like KISS Alive Forever (by Curt Gooch and Jeff Suhs), Behind The Mask (by David Leaf and Ken Sharp), and Nothin’ To Lose (by Sharp with Stanley and Simmons). These books include tales from many of the KISS road crew, so that aspect of KISStory will largely be bypassed here for the sake of keeping this piece a little shorter.

“We drove across Canada in a station wagon in the worst cold I’ve ever felt, but it didn’t matter. It was a thrilling experience for us.”

Gene Simmons

“Sometimes we would drive 17 hours to a show, get out of the car, run into the back door of the club, slap on make-up and go out on stage. And we were losing money with every show. Bill Aucoin financed the whole thing with his American Express card, which became completely worthless after a few months.”

Paul Stanley

The man most responsible for honing KISS’ show and taking them around North America in a beat-up van was Aucoin’s protégé Sean Delaney. In rehearsals he would be the tireless taskmaster that helped define the KISS characters, dyeing their hair blue-black, giving them signature lines and moves, and recording the band’s rehearsals on video for them to review their performance and work on their choreography and personalities.

“Do demons talk to you? No, they growl but they don’t talk. Ace would have opened his mouth and gone, ‘Ha!’ Peter was way back at the drums, cats don’t talk to you. Paul had to learn exact lines. I used to work with him on ‘How ya doin’?’ […] Gene would come out walking like a monster, and he’d walk back like a human, and I’d go, ‘You can’t do that! You have to be this thing.’ So I was their mirror and I did that twenty-four hours a day.”

Sean Delaney

“Sean played a major part in getting our show together. I don’t think he ever got the credit that was due him as a songwriter or what he added to the shows, the costumes, the choreography. He was a major, major contributor to all that shit.”

Ace Frehley

Meanwhile, Bogart at Casablanca would ceaselessly work on the hype of KISS. One of the early pushes was the nationwide kissing contest in which couples would compete for longest continuous kiss. To go with the event, KISS reentered Bell Sound with Kerner and Wise on 26 April to rewrite, rearrange, and record a cover version of the 1959 Bobby Rydell song “Kissin’ Time” for a single release. The band had reluctantly agreed to this promotion scheme on the condition that the song would not be added to their album, but it soon was. This ultimately diluted the impact of the vinyl album’s side B by pushing “Deuce” out of the opening slot, but this is the way the Kiss album would forever since be known.

Larry Harris was an important man at Casablanca Records as Senior Vice President, and he worked closely with Neil Bogart on everything that had to do with promoting and selling KISS. In later years he would make no bones about Casablanca bribing KISS onto radio by paying key radio personnel to play the band, an admittedly industry-wide practice of payola through either cash, credit cards, drugs or services. Harris would be equally blunt about the earliest KISS stunt of “Kissin’ Time” and the kissing contest:

“We would arrange for radio stations throughout the country to compete in a huge national Kiss-Off. […] Neil loved it. KISS hated the thought, however. They and their producers, Kenny Kerner and Richie Wise, were dead set against it; they didn’t want to record a cover song when they were perfectly capable of writing their own material. […] After his cajoling had failed, Neil told them, ‘Look, either you record the song or we’ll pull our support for you.’ It was pure bluff. […] We rush-released ‘Kissin’ Time’ as a single and, in direct violation of Neil’s promise, we included it on all new pressings of KISS’ first album starting in June.”

Larry Harris

The KISS tour in 1974 zig-zagged across the United States and Canada on the basis that KISS would play anywhere, with anyone, as long as they could get there on time. In early August they took a brief break from the road, because their record label Casablanca ordered them back into the studio to record a follow-up to their already failing first album.

With the working title The Harder They Come set for the new record, KISS rushed to compose some new songs as well as turning to a batch of earlier songs that were not recorded for their debut. The latter included “Watchin’ You” and “Let Me Go, Rock ‘n’ Roll” (previously known as “Baby, Let Me Go”). The new entries counted among them “Got To Choose”, “Hotter Than Hell” and “Mainline” (by Stanley), “Parasite” and “Strange Ways” (by Frehley), and “Comin’ Home” (by Stanley and Frehley). Simmons would later claim that it was hard to write while on tour, no doubt because he preferred to chase girls, and managed only the new song “All The Way” while also resurrecting his old tune “Little Lady” as “Goin’ Blind”.

Recording of the album that would become Hotter Than Hell took place at The Village Recorder in Los Angeles, California from 16 August into early September 1974, again with producers Kenny Kerner and Richie Wise, and with engineer Warren Dewey again helping out at the console and tape machines. It is certainly a classic for KISS fans, but it was and is an album with a very problematic production.

“Richie and I had moved to LA, so we wanted the band to record their second album there. […] The band didn’t like it out in LA. They didn’t drive, which makes it difficult to get around. Paul’s guitar was stolen on the first day of recording.”

Kenny Kerner

“I hated the sound of that album. […] I wanted to make a harder, more forceful record. I thought the guitars on the first album weren’t distorted enough. […] There were some good songs on Hotter Than Hell, but a better recording would have served it better. […] I take full responsibility for the failure of that album, bad sound decisions, and bad creative decisions. I was very disappointed in the record.”

Richie Wise

“Hotter Than Hell was the first album where we couldn’t rely on material that we had written in high school. Although there were some leftover songs on the album from our club days, it really came down to writing a new batch of songs, which was daunting. […] We were recording the album at Village Recorders in Santa Monica, and we wanted to make a sonically more accurate record of who we were, but unfortunately that got lost in the mix. It’s not a great-sounding album, but the material is really good. […] Unfortunately, the people that we were working with were probably not the right people to be doing it with.”

Paul Stanley

Painfully overdriven and compressed, the unpleasant sound of Hotter Than Hell must undoubtedly be blamed on producers Kerner and Wise. They would in later years complain that the studio didn’t work properly and that speakers were substituted regularly. But this is a strange complaint about one of the top-line studios in LA for records and movie soundtrack productions. Furthermore, the producer duo had showed their hand with the recording of “Kissin’ Time” in New York earlier in the year: The grating audio was already apparent in that recording, proving that Kerner and Wise wanted to rough up the KISS sound but didn’t know how to do so.

Hotter Than Hell appealed mostly to the people who were already into the band’s first album, an admittedly small group, and it was also clear that a lot of people who enjoyed KISS’ live shows were not at all taken with their presentation on vinyl. The question of how to capture KISS’ forceful performance and expand their audience would be a major theme for the year ahead, a challenge that would lead to working with both Eddie Kramer (for the first time since their 1973 demo) and wunderkind producer Bob Ezrin (for the first time ever).

KISS continued to build a following on the road, touring intensively through the end of 1974 and into early 1975. But sales success eluded them, their first two albums sold modestly and there were no hit singles in sight, and as the new year approached it also became apparent that their record company Casablanca was in trouble.

1975

KISS was upset that Casablanca had not paid them royalties according to the agreement in the production contract between the label and Aucoin’s Rock Steady Management. Casablanca, on their side, insisted that funding album productions and keeping KISS on tour was costing way more than what they owed the band in royalties. Not only manager Bill Aucoin, but also the Casablanca company, was called on to finance the show and run the touring. From Casablanca’s point of view, KISS owed them money and were not entitled to pre-agreed royalties until the debt was covered.

Even so, as KISS now had two albums under their belt and their following was growing thanks to their engaging live shows, the band and their management were beginning to think that maybe Casablanca did not have what it took to break KISS big. And at this point, as 1974 turned into 1975, other and bigger record companies were starting to take notice of KISS and their record company situation.

From Aucoin’s point of view, even as he would always profess his support and sympathy for the pioneering Casablanca president Neil Bogart, it did seem that a manager’s due diligence was to look for better options. A particularly worrying sign was the fact that the distribution deal between the independent Casablanca and the major player Warner Brothers had fallen through in 1974 when Bogart got wind of Warner’s promotion priorities. Stan Cornyn, then Executive Vice President at Warner, explains the incident:

“Neil’s brother-in-law, Buck Reingold, who worked for him, was in our offices. Bucky overheard the promotion weekly call, which would go out to thirty people on the line with our home office talking to them and setting priorities. He found out that KISS records were not a number one priority at Warner Brothers. KISS was a number one priority at Casablanca but wasn’t top priority at our label because we had thirty other records to promote and evaluate. I think maybe the promotion weekly phone call was taped because he had pretty good evidence. He played it for Neil and a charge was made against Warner Brothers.”

Stan Cornyn

“I went into Neil’s office and told him, ‘If we stay another year with Warner Brothers we’re gonna go down the drain.’ He said, ‘What do you mean?’ I said, ‘I paid someone off on the Warner Brothers staff to tape the weekly promotion conference call to find out what they were saying.’ ”

Buck Reingold

“When Neil heard a tape of our weekly ‘promo hotline’ community call to all promo personnel across the country, he heard our promotion head, Gary Davis, casually mention that Warner Brothers’ label releases deserved staff concentration more than any one-shot release. Bad wording, Gary. Neil heard only that Warner Brothers’ priority was being placed on their own acts, and Casablanca releases were being pushed less by our field forces.”

Stan Cornyn

The first KISS album sold about 75 000 units on its initial release, while Hotter Than Hell would climb to about 100 000. It was all well short of expectations, and Casablanca also heard alarming complaints from their retail contacts: When KISS albums were ordered to the stores, they would never be shipped through the Warner distribution pipeline. In short, stores wanted to sell KISS but were unable to get albums.

“Over one hundred thousand of our units were back-ordered due to pressing-plant issues. […] Since the plants they were using could not keep up with all the orders, they were pressing Warner-owned product before they pressed product from the subsidiary labels. […] First, we’d been ignored by promotion, and now we were getting screwed by production and sales.”

Larry Harris

Casablanca were confrontational about the words used in the taped promotions phone call, and Warner’s top people had had enough of Casablanca and their sinking of funds into the unprofitable KISS. A parting of ways was agreed on and Casablanca was released from the distribution agreement with no penalties for the debt incurred. With the Warner Brothers organization out of the picture, Casablanca now had to cobble together its operation and finances through independent distributors, and KISS’ main manager Bill Aucoin was looking on with great worry as it seemed that the window of opportunity for a breakthrough was not going to stay open much longer.

At the same time, KISS’ co-manager Joyce Biawitz had entered a romantic relationship with Casablanca president Neil Bogart, who would sometimes have diametrically opposing interests to those of the band. Now things were getting complicated, and the fate of KISS was hanging in the balance.

“We were ready to leave the label because we weren’t getting our royalties. Around that time, we weren’t exactly a hot item, but there were offers from other labels. […] There was a gray area because Joyce was involved at that point with Neil, and it’s hard when that’s also part of the management team.”

Paul Stanley

“Joyce started going out with Neil, which immediately made it a conflict of interest. […] We had a meeting in my apartment in Los Angeles with the whole band, Joyce, Bill, Richie and me. We were discussing a substantial offer from Atlantic Records. They offered us a million-dollar deal to take the band, me and Richie as producers, Bill and Joyce as managers, the whole package. […] Nobody was happy with the way things were going, and they were open to the possibility of going with another label. […] The next day, Neil Bogart knew everything that had happened at the meeting. He fired Richie and me and decided to produce the third album himself. […] He wanted to buy the management out from Bill. There was only one possible way for him to have found out about that meeting and that was through Joyce.”

Kenny Kerner

The LA meeting that producer Kenny Kerner describes was most likely held around 1 February 1975, as KISS was on tour in California at that time. Bogart made the immediate move to take control of KISS’ next recording sessions himself, and the temperature between Casablanca/Bogart and KISS/Aucoin got unprecedentedly frosty.

Aucoin ultimately bought Biawitz out of their management company, and she would soon become Joyce Bogart. KISS stayed loyal to Bill Aucoin as their manager but also stayed with Neil Bogart and Casablanca rather than go for another label’s offer. The road ahead, however, was anything but clear and straight, and the tension between KISS and Casablanca would not completely subside until the end of 1975.

With Hotter Than Hell sinking like a stone in the sales charts, Casablanca needed another album from KISS quickly to keep their financing going through advances from the myriad independent distributors lined up. This would only work if a new KISS album arrived with the regularity of twice a year. Some demo work was done in Larrabee Studio in Hollywood on 24 and 25 January 1975, which included an early recording of the anthem song that Bogart had suggested KISS needed, “Rock And Roll All Nite”.

Without really being prepared, the band then entered Electric Lady Studios in New York City on 8 February for two weeks of recording. The sessions were ostensibly produced by Casablanca president Neil Bogart, but the sound of the album probably owes more to KISS doing what KISS did and in-house engineer Dave Wittman (who had worked on the KISS demo in 1973) ably capturing their hasty performances on a warm-sounding tape.

“We did the whole album at Electric Lady in Studio B. It was a funky little room. KISS did the rhythm tracks live. They would get the songs in like two or three takes. KISS were always well rehearsed, everything went real smoothly.”

Dave Wittman

“I attended some of the sessions, but I don’t remember much more than the constant haze of pot smoke that drifted around the control room. The weed smoking was primarily Neil’s doing, as Paul and Gene were notorious teetotalers when it came to drugs and Ace and Peter tended to drink and take drugs only when they weren’t with their bandmates.”

Larry Harris

“Neil was smoking a lot of pot in those days, and I know when you smoke pot you can’t hear things correctly. Everything sounds great. And then the next day you come in and go, ‘Holy shit, that’s terrible!’ because pot makes things sound good. […] But I just don’t think Neil went into it with a producer’s attitude.”

Peter Criss

“Neil didn’t do much. He sat in the room and tried to keep us from doing too many takes. Not because he thought he could capture something special in an early take – just to save money by getting the album done more quickly.”

Paul Stanley

There were still leftovers being employed on the album that was recorded with the working title KISS At Midnight. “She” and “Love Her All I Can” went all the way back to Wicked Lester. Paul Stanley wrote the new songs “Room Service”, “C’mon And Love Me”, and “Anything For My Baby”, while Gene Simmons came up with “Two Timer” and “Ladies In Waiting”. Ace Frehley chipped in with “Getaway” (sung by Peter Criss) and the acoustic intro to Stanley’s “Rock Bottom”. And ultimately the album’s most famous track would be the Stanley and Simmons concoction “Rock And Roll All Nite”.

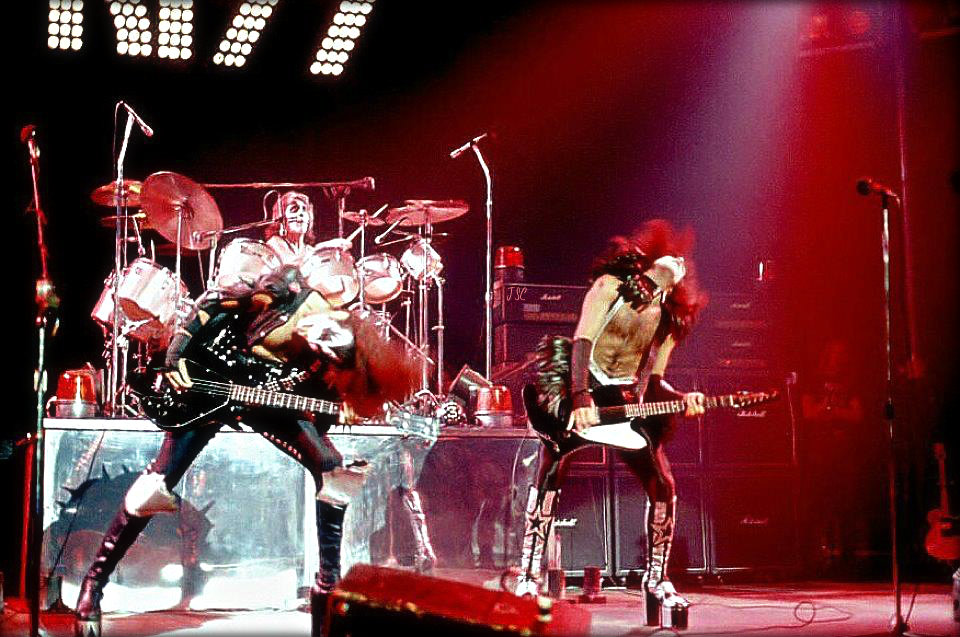

Released as Dressed To Kill on 19 March 1975, the album would not provide any hit singles and would not sell much more than the previous two, but it was the third album in a year that fleshed out a concert setlist with enough great songs to make KISS a very viable live attraction. The band’s status was now changing from support act to headliner, and not just in theaters: KISS began to sell out arenas, particularly in the American Midwest. Detroit was one of the cities that took to KISS early, and by the spring of 1975 they were headlining at the renowned Cobo Arena, an event that was recorded on 24-track for an upcoming live album.

The story is well known: KISS Alive! saved KISS, and it saved Casablanca too. The record became a big seller, quickly surpassing Gold status to hit the Platinum mark at one million units and still climbing, establishing KISS as rising stars. But how did KISS, a band without hits or great album sales, come to gamble on a double live album at this point? And why did that gamble work out?

In the aftermath of the early 1975 bust-up between the KISS camp led by Bill Aucoin and Casablanca led by Neil Bogart, KISS signed a new contract with Casablanca on 1 May. As their previous contract had actually been a production agreement between Casablanca and KISS’ management, this May 1975 deal was their first proper record contract signed in their own names: Gene Klein, Stanley Eisen, Peter Criscuola and Paul Frehley. Like the previous agreement, it stipulated that KISS was to deliver a new album approximately every six months, so it was a given that a new record had to be ready for late 1975.

It is a convenient and often repeated justification that the band thought their popular concerts would make a live album work as the solution to their average record sales. However, no rock band had ever made their breakthrough with a live record, which was considered to be a throwaway kind of product. The truth is that Aucoin was already courting Bob Ezrin to produce the next KISS studio album, and the manager was still unconvinced of Casablanca’s abilities, if not their commitment. The album Ezrin was to make with KISS would not be ready for release until early 1976, so KISS Alive! can reasonably be considered a contractual obligation and stop-gap to fulfill the promise of delivering a new record about six months after Dressed To Kill.

“I was disappointed that I didn’t get to produce KISS’ first album since I did their demo, which got them their record deal. Politics prevailed. The first two albums were okay. I’m pretty sure the band wasn’t totally happy with the sound of them.”

Eddie Kramer

Eddie Kramer was called in, and he actually turned down the opportunity to produce the first Boston album to rather record four KISS concerts in the spring and summer of 1975: Detroit (Michigan), Cleveland (Ohio), Davenport (Iowa), and Wildwood (New Jersey). These recordings would subsequently be augmented by extensive re-recordings and overdubs at Kramer’s preferred Electric Lady Studios in late July into early August, and the tapes were then mixed by Kramer for a September release.

This was all going on at around the same time that KISS started writing and rehearsing with Bob Ezrin for their next studio album, which is a clear indication that KISS and Aucoin did not really view the live album as a last-ditch effort to make or break the band. They would do a record with Ezrin, but it was not a given that they would stay with Casablanca. The specter of the early 1975 problems was still haunting the making of KISS Alive! in late summer. But something was about to work unexpectedly well.

“Eddie Kramer was great at helping to create Alive!, and I say ‘create’ because the album was really an enhanced version of what took place. […] There was some controversy about that, but truth be told it’s the most accurate-sounding live album of its time.”

Paul Stanley

“I don’t care how great you are, there is no way you can do the kind of stuff KISS does onstage and come off sounding in tune and in time. […] The boys were very cool about it. […] We fixed what we had to fix and left what was great. […] The reason for the success of the record, if I could analyze that, would be the fact that they toured very heavily in the Midwest and the South for two years.”

Eddie Kramer

“We were selling out concerts. We couldn’t find groups to play with. We were thrown off an Argent tour, a Savoy Brown tour. Black Sabbath threw us off their tour. It was a live-or-die situation for Casablanca. […] Recording a live album when you really haven’t even made it, we hadn’t even had a Gold record. […] I think that KISS Alive!, sonically, is what the band is about.”

Gene Simmons

In late 1975, back on the road, the KISS show was entering its consolidation phase: The setlist was established as approximating the KISS Alive! album, and there were now the levitating drums, the smoking guitars, the flaming pyro, the concussion bombs, the confetti storms, the smashing of guitars, the fire-breathing and the blood-spitting.

But there was still the unresolved issue of Casablanca’s failure to pay KISS any royalties at all. On 11 September, Bill Aucoin sent a letter to Casablanca and announced the termination of the 1973 production agreement between the record company and the manager.

“Eventually, when we didn’t get any royalty payments, I had to stand up for the band. That turned into a major fight, and I could have easily left Casablanca. […] But I really had no reason to leave Neil. I just had to straighten out this business end.”

Bill Aucoin

The contract that KISS had signed with Casablanca on 1 May 1975 specifically stated that it replaced the original 1973 production agreement between Casablanca and Aucoin, so quite how the manager could threaten to terminate that original agreement is unclear. Likewise, the new contract also stated that Casablanca did not have to make their first royalty payment to KISS until the end of 1975. The new contract bought Casablanca time.

But in the meantime, Aucoin was setting up KISS with Ezrin and possibly hoping that these sessions could potentially tempt bigger record companies with a prospective KISS/Ezrin collaboration in the wake of what now looked to be their breakthrough KISS Alive! album.

To put further pressure on Casablanca, Aucoin openly, and arguably in breach of the KISS/Casablanca contract signed in May, offered KISS to both Atlantic Records and Warner Bros in early October. In short, this was a staring contest where Aucoin bluffed. The other contestant, Bogart, simply did not want to run the risk of losing KISS only to see them become a success for another label.

“Neil blinked and cut KISS and Aucoin a check for two million dollars. […] Aucoin and KISS were happy, for obvious reasons, but Neil was physically drained.”

Larry Harris

“This was back in ’75 when two million was like ten million. All I can remember is staring at those zeroes. I sat there and kept counting the zeroes.”

Bill Aucoin

As soon as KISS Alive! started selling like hotcakes, and a live version of “Rock And Roll All Nite” became KISS’ first legitimate hit, all the points of contention were moot. The work and investments had paid off. What would seem like an overnight sensation to many observers, was in fact the fruit of two years of nerve-racking gambles and blind faith. Both KISS and Casablanca were now a certified commercial success.

“I always had faith in the band. I knew it was going to happen eventually, but it was after the first live album that I knew we’d finally broken through. It captured what we were doing, and we began to see a difference in audience reaction. It was then that we could look out from the stage and see that the place was packed.”

Paul Stanley

KISS had arrived. KISS Alive! was a hit. Their nationwide arena concerts were selling out. So what next? KISS had started working with producer Bob Ezrin in the late summer of 1975, preparing for what was set to be an intensive few weeks of recording in early 1976. They did not know it yet, but KISS was on the threshold of creating their masterpiece, one of the greatest records not just in their own catalog but in 1970s rock music.

That is a story for later, as Destroyer turns 50 in 2026!

Sources: KISStory (1994), KISS & Tell (Gordon G.G. Gebert & Bob McAdams, 1997), Black Diamond: The Unauthorized Biography of KISS (Dale Sherman, 1997), KISS and Make-up (Gene Simmons, 2001), KISS Alive Forever (Curt Gooch and Jeff Suhs, 2002), KISS Behind the Mask: The Official Authorized Biography (David Leaf and Ken Sharp, 2003), The KISS Album Focus: Kings of the Night Time World (Julian Gill, 2008), And Party Every Day: The Inside Story of Casablanca Records (Larry Harris, 2011), No Regrets: A Rock’n’Roll Memoir (Ace Frehley with Joe Layden and John Ostrosky, 2011), Makeup to Breakup: My Life In and Out of KISS (Peter Criss with Larry “Ratso” Sloman, 2012), Nothin’ to Lose: The Making of KISS 1972-1975 (Ken Sharp with Paul Stanley and Gene Simmons, 2013), Face the Music: A Life Exposed (Paul Stanley, 2014), Shout It Out Loud: The Story of KISS’ Destroyer and the Making of an American Icon (James Campion, 2015), www.kissfaq.com , www.kisstimeline.com